Hummingbird Banding?

The Western Winter WINs were invited alongside the general public, to get a close-up look at migrating hummingbirds on Saturday 26th March. Staff and volunteers from the Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory were due to capture, band, weigh, measure, and release them as part of long-term studies along the vital migration route at San Pedro House visitor centre, near Sierra Vista.

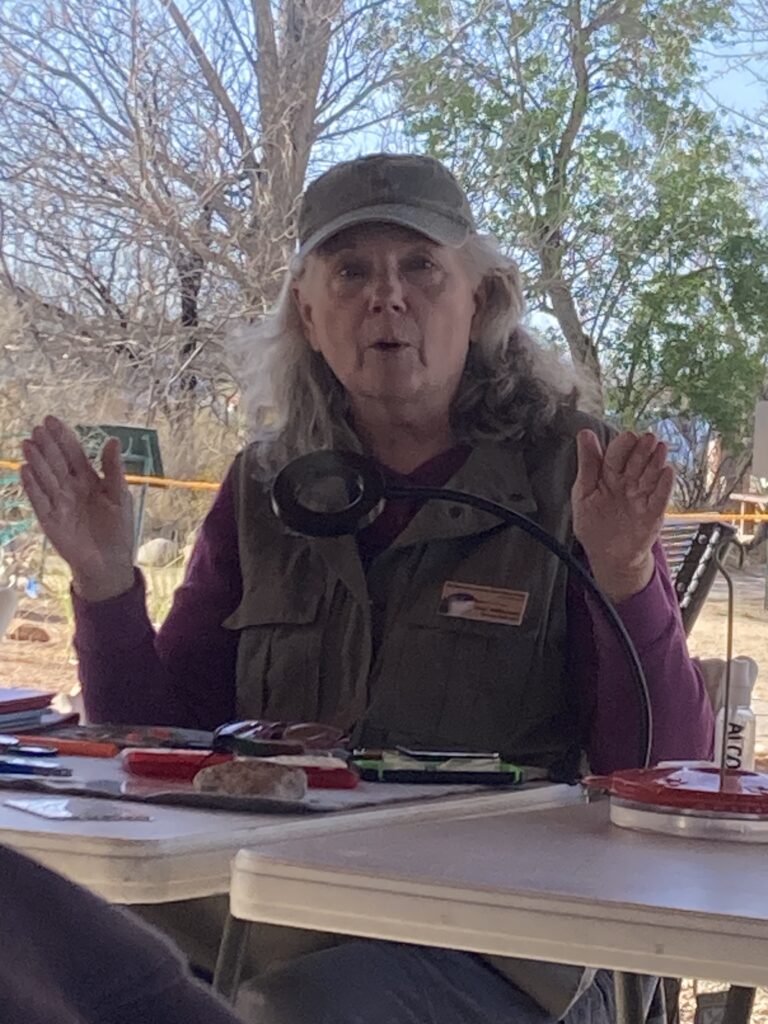

We duly took our places in the covered seating area, surrounded by the lush green vegetation which forms a green ribbon along the San Pedro River, as one of the members of the Banding Team explained the procedure.

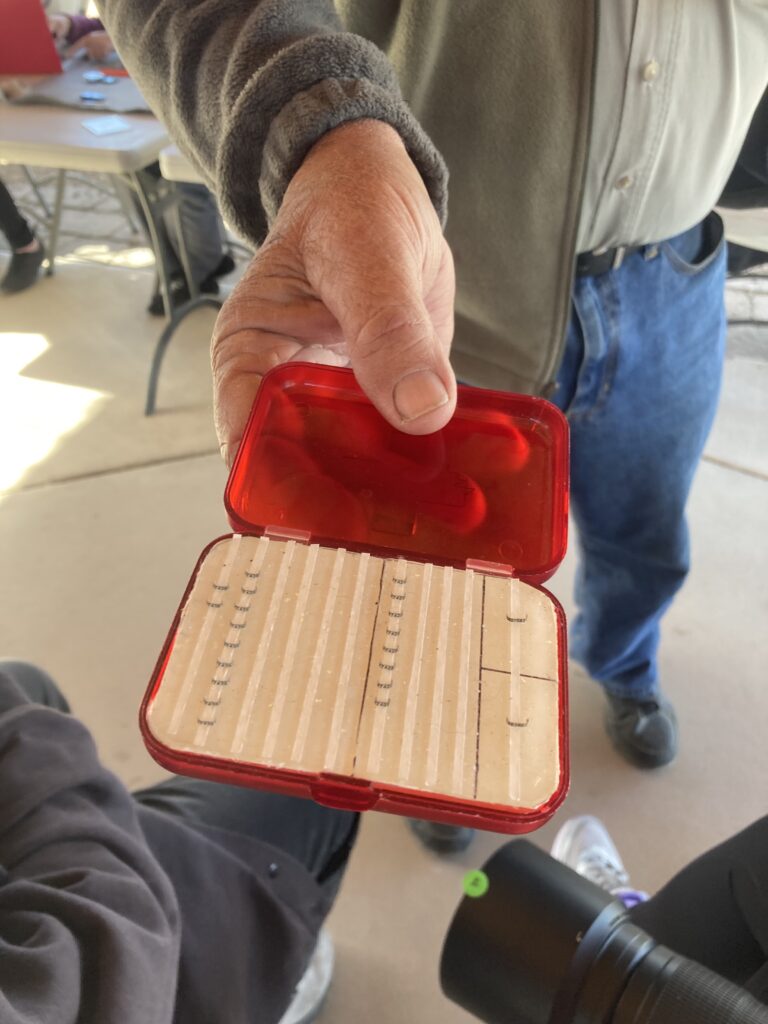

The bands have a number, and that number is taken from a centralised data base, so wherever and whenever the individual bird is caught again the information can be added to the knowledge-base. Over the years the North American Bird Banding Program has been collecting and collating the data, with some interesting results.

To describe the delicate procedure one of the banding team held up a felt humming bird, the tiny animals generally weigh 3 grams but the larger ‘Anna’s can weigh 4 grams.

The experts explained that banding, also known as ringing, is one of the best tools we have to help us understand the lives and travels of birds. By using numbered bands like these to identify individual birds, we can learn much about life span, reproductive cycles, timing and routes of migration, and the importance of particular nesting, wintering, and migration stopover sites.

Apparently, banding studies can act as a diagnostic tool for the health of bird populations which in turn may reflect the general health of the environment. Banding is particularly useful in studying highly migratory species, which include most of the hummingbird species found in the United States and Canada. Much of what we know about hummingbird migration comes from banding. For example, each spring and fall some Rufous Hummingbirds must migrate at least 2700 miles between their nesting and wintering grounds; long-term banding studies show that they tend to follow the same routes and arrive at stopover sites within a few days of the same date each year.

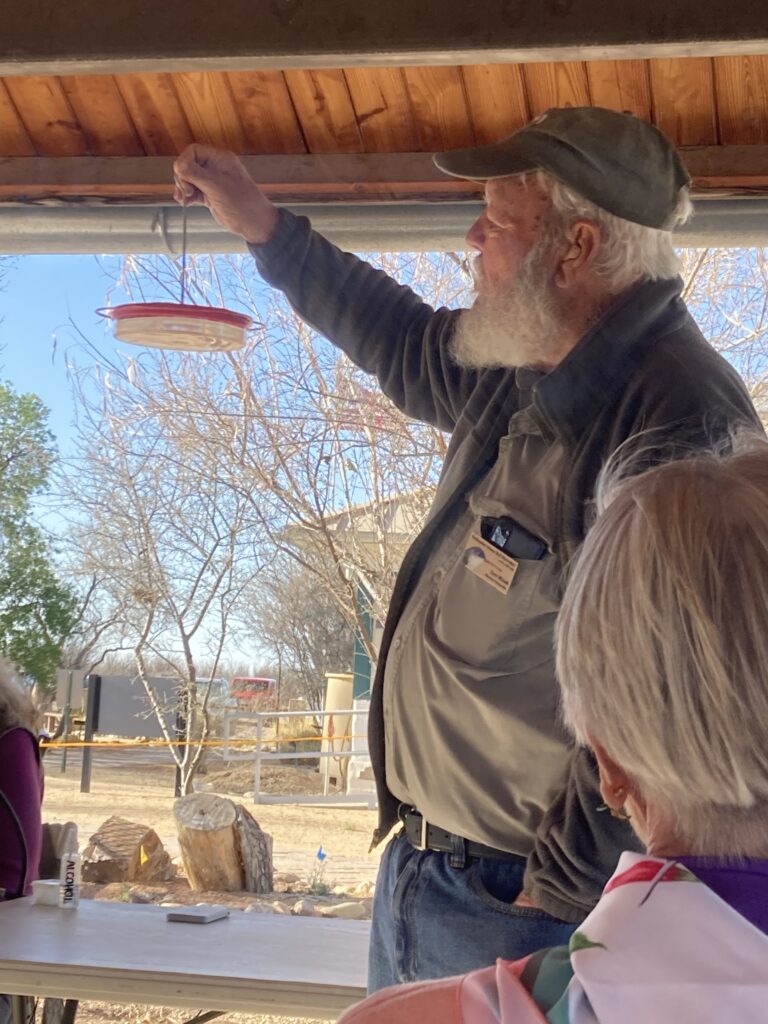

Our experts then turned their attention to hummingbird feeders, they advocated a 1 part sugar and 4 parts water mix. There was much discussion and many questions about the type of water and sugar, as well as the method of making up the ‘nectar’ solution.

Ordinary tap water was recommended, unless one lived in an area where the city added large amounts of chorine or other chemicals. However sugar should be top of the range branded white granulated sugar. Many ‘own brand’ and other lesser known sugars may not be the 99.7 or above. Where there is an impurity of greater than 0.3 per cent, that may adversely affect the health of the hummingbird. The impurities may be dust, spores or even insect parts that have slipped through a less rigorous manufacturing process. While this sugar may be safe for human consumption, Hummingbirds have a very high metabolism and must eat all day long just to survive. They consume about half their body weight in bugs and nectar, feeding every 10-15 minutes. If you or I were to consume almost half our weight of the lower quality sugar mix every day, the impurities would soon be causing issues in our bodies too!

Our hummingbird banding team went on to discuss how they would adjust the strength of the nectar mix according to the temperature, in very cold weather they might give a slightly sweeter mix: 3 parts water to 1 part sugar. While in high summer, if the thermometer was up in the high 90’s or over 100°F they would add water, up to 5 parts water to 1 part sugar, but keeping within those parameters.

I looked at my watch, I was starting to think the Banding Team were playing for time! Sure enough, the wild humming birds were not playing today, while we had been entertained by all the hugely interesting scientific facts and as the the wind was getting a little chilly and the audience was thinning, we were informed that other members of the banding team had been checking the humming bird traps regularly, and not one had been sprung!

I am a veteran of wild animal shows, as a sailor in the Bay of Gibraltar, one always likes to introduce people to the sight of dolphins playing in the bow wave, or under the stern of the sailing boat, leaping singly or in groups of three or four, whole families together. So I could well understand how that the birds were not held captive for our convenience! As the sun was slipping down towards the horizon, soon the last of the WINs slipped out and away just in time for dinner.

Leave a Reply